Walnuts have been part of the human diet for over 8,000 years. The Persian walnut was first cultivated in Babylon around 2000 BCE, refined by Greeks and Romans into the large, thin-shelled “royal nut,” and later carried by Spanish missionaries to California, where it became today’s global standard.

Meanwhile, Africa has nurtured its own version for millennia. The African walnut (Tetracarpidium conophorum) is not a tree at all but a climbing rainforest vine, native from Nigeria to the Congo Basin. Unlike the intensively bred Persian walnut, the African walnut has been grown in a more traditional, low-key way. Farmers simply let it twine up cocoa or kola trees, harvesting the small, hard nuts for food, trade, and ceremonies; a practice that has remained unchanged for centuries.

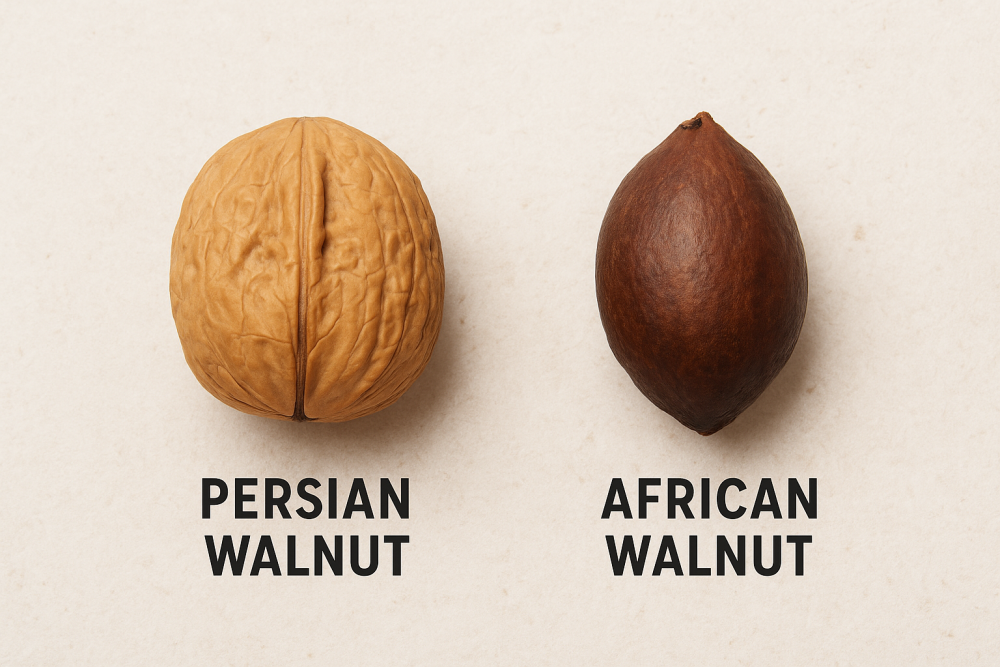

The African walnut produces small green pods, each hiding a hard, dark-brown nut just a centimeter or two wide. Inside lies a creamy kernel, rich in oil and nutrients, but highly perishable; it must be eaten within a day or two of roasting or boiling.

In southern Nigeria, the nut is a common street food, sold freshly boiled in markets and shared at weddings or naming ceremonies, much like kola nuts as a gesture of friendship and goodwill.

Nutritionally, African walnuts are impressive: high in omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, vitamin E, magnesium, and rare antioxidants. Traditional Yoruba and Igbo healers once used them in “brain tonics,” fertility remedies, fever teas, and even twig chews for toothaches. Today, they still appear in baby porridges, fertility drinks, soups, and hair oils across West and Central Africa.

The Persian walnut (Juglans regia), sometimes called the “English” walnut, grows as a tall deciduous tree up to 30 meters high. Its smooth, light-brown shell is larger and thinner than that of the African walnut, making it easy to crack open and store for months.

This is the walnut most people know; the one found in supermarkets worldwide. First cultivated in ancient Babylon, it spread via Greek, Roman, and Arab traders, eventually taking root in California, which today produces about half of the global supply.

Persian walnuts are celebrated for their health benefits: rich in polyphenols, melatonin, and alpha-linolenic acid, they support heart health, lower blood pressure, and reduce inflammation. Across cultures, they have been used in medicine and cuisine, from Roman ulcer remedies to Chinese kidney tonics, from Italian nocino liqueur to modern walnut butters, flours, and oils.

The African walnut is known by many names: asala/awusa (Yoruba), ukpa (Igbo), ukwa (Igala/Idoma), ekporo (Efik/Ibibio), okwe (Edo), kaso/ngak (Cameroon), and awusa again in Sierra Leone, carried back by returnee settlers.

In everyday cooking, these names follow the nut into dishes. In Nigeria, asala is added to peppered rice, soups, or mashed into baby porridges. Edo kitchens stir okwe into palm-oil stews, while Hausa vendors roll it with honey into sweet balls. In Cameroon, kaso is cooked into ndolé, while in Gabon, conophor sauce features on the table.

Today, African walnuts remain a regional treasure, while Persian walnuts dominate international trade. Yet their stories are complementary: one rooted in ancient global agriculture, the other in deep African cultural heritage.

Though you may not find African walnuts outside their home region, the more familiar Persian walnut can substitute in recipes; pounded into porridge, blended into smoothies, or sprinkled over salads. From raw snack packs to walnut butter, meal, and oil, they’re widely available.

One day, perhaps, the African walnut too will find its way onto shelves across the continent and beyond, celebrated not only as a nutritious food but also as a living link to African culinary traditions like the bambara.

Note: Other trees, such as Coula edulis and Lovoa trichilioides, are sometimes called “African walnut” in the timber trade, but their nuts are not widely eaten

Add your reply

Replies